There is no need to cover the juicy details of being out on the road in a hip new rock/blues band during the sixties. It's a fantasy which has been romanticized numerous times in movies, and the various entertainment trades media.

In 1966, the Butterfield band doesn't own the slick Pierre Cardin uniforms that the Beatles wear on stage, nor do they dress up in the premeditated

'working class' outfits that so many of the British invasion bands are assigned by their management.

At this point, they are approaching mid-level rock star status in the emerging counter culture music scene in the United States, and looking forward to success abroad. In spite of the perks that go with a critically acclaimed band of young musicians on the road, Paul Butterfield's band looks like a group of college kids getting together to play some great music. There is nothing pretentious about their appearance or there music.

However, there is a another side to being applauded by your public and the media. When a band goes out on the road it serves a few purposes. Artistically, a band works on its material, tests new songs, works on their sound etc.. (Butterfield rehearsed his band six days a week.) From a business point of view, it's about promoting a product, usually a recent album, or maybe a soon to be released album, but it is about selling a the music. While the band is idolized by a growing fan base, they don't have any mainstream hits, and that influences the size of venues they play. Unlike most of the blues/rock bands coming over from Britain, the Butterfield band is still traveling, and unloading their own gear from a used Econoline van.

It seems that the lower a band is on the food chain, the longer they are out on the road. The lifestyle has a lot going for it when you are in your early twenties and single, but it also comes with a price tag. There are issues with sleep, poor diet, little physical exercise, and a host of other distractions from the boredom associated with traveling like a group of door to door salesmen.

It isn't like they have the perks of a hit record as their contemporaries

The Rolling Stones or

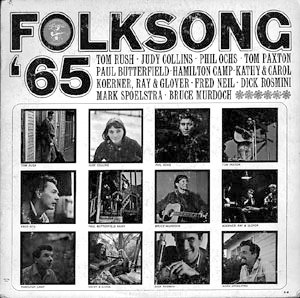

The Animals do. Those blues based bands stay in better hotels, play to thousands of screaming kids, and enjoy many of the condiments available to artists of that position in the food chain. However, they are in good company. Other ambitious acts like Van Morrison, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Tim Hardin and a host of artists who are eager to become household names, are working the same circuit.

Even though they earn some critical success with the release of

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, they are still playing, small bars, roadhouses, coffee houses, and almost any venue willing to let them promote their music. Then a personnel problem is presented to Butterfield; Sam Lay is stricken with pleurisy (an inflammation of the lining around the lungs). According to Lay he thinks his illness is the result of becoming overheated while on stage, and when he goes out into the cold north east night air, his body reacts with the pleurisy. It is possible, but pleurisy is the result of a virus, and he could have contacted that anywhere.The end result is that he can't play in the band, and Butterfield has to hire a new drummer. For years after Lay leaves the band, there are sketchy reports of him leaving because he had been

wounded in a gun fight, or

he shot himself in the foot with his own gun. All of them romantic tales of life in a blues band.

107)

Another one of Butterfield's skills is his ability to pick excellent musicians for his bands. Initially, he doesn't want to hire Mike Bloomfield, but like a wise leader he understands the importance of surrounding yourself with strong talent, and at the insistence of Paul Rothschild he hires him. Sam Lay had been an excellent choice for the early band. He had played with some

heavy hitters in the blues world, people like Little Walter and Howlin' Wolf plus a host of other acts. Known for his unique energetic style which earns the title of the

"Sam Lay double shuffle" he is no slouch at driving the band. In fact, for Buttefield, Sam Lay is just the first of a long line of superbly unique drummers that he hires. As Geoff Muldaur noticed, Butterfield had an obsession with the foot. (bass drum)

Lay's illness, and departure from the band is a casualty of life on the road. It's also the first causality of the Butterfield lineup. However, Butterfield already has his sights set on another Chicago drummer. Billy Davenport has been working with Chicago jazz bands a fan of Art Blakney's drum roll, and the big sound of Louis Belison's double bass drum knows his way around a drum kit, and after some relentless persuasion and help from Bloomfield, Davenport is hired.

So, with the drummer issue resolved, the band can regain a renewed level of stability again. In spite of their impending success in the bigger markets, they aren't playing big rooms.

Born in Chicago is a hit on FM radio, and is definitely an important break for the band, but it isn't a mainstream hit. So, the band is playing smaller venues, sometimes two different gigs in a single day. They are known nationally, and thank God, some fans are devoted enough to haul massive reel to reel tape machines into these, sometimes remote locations, and record them.

They are working a number of clubs in and around the New York area, and often driving up to Boston where there is a busy folk scene close to Harvard. One of the places they frequent is a coffee house called The Unicorn. It's a small picturesque room with beautiful pine-paneling in a basement opposite the Prudential Center on Boylston Street. The Unicorn doesn't sell anything more intoxicating than coffee, and tea. For a dollar or two, you can see The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem or maybe Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell or Tim Hardin. It's a small room best suited for artists who are on their way up or on their way down.

They are working a number of clubs in and around the New York area, and often driving up to Boston where there is a busy folk scene close to Harvard. One of the places they frequent is a coffee house called The Unicorn. It's a small picturesque room with beautiful pine-paneling in a basement opposite the Prudential Center on Boylston Street. The Unicorn doesn't sell anything more intoxicating than coffee, and tea. For a dollar or two, you can see The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem or maybe Van Morrison, Joni Mitchell or Tim Hardin. It's a small room best suited for artists who are on their way up or on their way down.

So, this is where

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band: Live at the Unicorn '66 originates. It is a bootleg recording, the sound quality is pretty rough, and I am glad I own a copy.

There are a couple of ways of looking at bootleg recordings of any artist. Unfortunately, the artist usually doesn't get any money for the sessions, nor they receive any royalties for the sale of the final product. However, if the artist is important because they make significant contributions to a genre, then the bootleg becomes a historical document. If you are a collector, as I use to be, or a fan as I still am, then bootlegs are a great part of your collection.

As for this show, because of the sound quality it doesn't do the band justice. It isn't edited, has a long introduction of sounds from the stage, and the audience which nobody wants to hear. If the recording were to be professionally remastered, it could be commercially viable, but as it is, this recording is a novelty.

When I first got hold of a copy of this show, it was on a C90 audio cassette, and then a couple of years later I was given it as a couple of CDRs. Now, anyone can either listen to the whole show on YouTube (I posted the link below), or you can download it. Don't waste your time with sleazy vendors online.

In closing, I want to thank the taper who had the foresight, or the impulse to haul a monster of a tape machine down to

The Unicorn that spring night in 1966. When that kind of effort is made to record a band, you have to believe they will be creating some great music that night.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band at The Unicorn Coffee House in Boston, Spring, 1966,

Look Over Yonders Wall, Born in Chicago, Love Her With A Feelin’, Walkin’ Blues, Don’t Say No

To Me, One More Heartache, Work Song, Thank You Mr. Poobah, Serve You Right To Suffer, Got

A Mind To Give Up Livin’, Walkin’ By Myself, Baby Please Come Home, World Is in An Uproar and

Got My Mojo Workin’,

Paul Butterfield harmonica and vocals, Billy Davenport drums, Jerome

Arnold bass, Mike Bloomfield guitar, and Elvin Bishop guitar and vocals (Don’t Say No To Me)

Muddy Waters is such an significant figure in the history of American Blues, Chicago Blues of the fifties, and then Rock/Blues of the sixties and seventies. He sets so many benchmarks over the course of his career, there are just too many to cover in this short blog.

Muddy Waters is such an significant figure in the history of American Blues, Chicago Blues of the fifties, and then Rock/Blues of the sixties and seventies. He sets so many benchmarks over the course of his career, there are just too many to cover in this short blog.

,+an+all-afternoon+affair+called+Bluesville.+The+band+was+filmed+by.jpg)